Positional asphyxia is a form of asphyxia which occurs when someone’s position prevents the person from breathing adequately, a risk carried along with the use of physical restraint.

The term, also known as postural asphyxia, came to be widely known across the world after the deadly arrest of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020.

Dr. Andrew Baker, the chief medical examiner who deemed George Floyd’s death a homicide, said in his testimony that Floyd died after police “subdual, restraint, and neck compression” caused his heart and lungs to stop.

The case sparked widespread protests and calls for reform in law enforcement practices to prevent similar incidents in the future.

As the conversation surrounding positional asphyxia continues to grow, it is essential for individuals, especially security professionals, to be aware of the risks and take the necessary precautions to prevent the risk of positional asphyxia.

With increased awareness and education, the hope is that the number of fatalities attributed to this silent killer will decrease in the coming years.

Training is absolutely vital in relation to any front-line staff who are involved in potentially confrontation situations not to hear that tragic utterance “I can’t breathe!” ever again, which has become emblematic of positional asphyxia after Floyd’s killing.

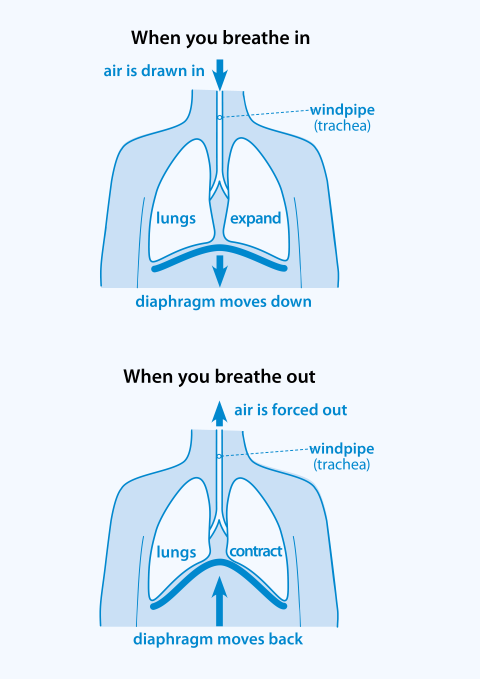

How the respiratory system works

Asphyxia is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body is deprived of oxygen. To understand positional asphyxia, we need to first look at how the respiratory system works.

Lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system, responsible for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air we breathe and the blood.

When we breathe in, air enters the body through the nose or mouth and travels down the trachea, also called the windpipe. The trachea then branches into two bronchi, one for each lung. These bronchi further divide into smaller bronchioles, which eventually lead to tiny air sacs called alveoli.

The alveoli are surrounded by a network of tiny blood vessels called capillaries. Oxygen from the inhaled air diffuses through the thin walls of the alveoli and into the capillaries. At the same time, carbon dioxide, a waste product of cellular respiration, diffuses from the blood in the capillaries into the alveoli.

Once the oxygen and carbon dioxide have been exchanged, the blood carries the oxygen to the cells throughout the body, while the carbon dioxide is carried back to the lungs. When we breathe out, the carbon dioxide-rich air is expelled from the alveoli, through the bronchioles, bronchi, trachea, and finally out of the nose or mouth.

The process of inhalation and exhalation is facilitated by the diaphragm, a large, dome-shaped muscle located beneath the lungs.

When the diaphragm contracts and moves downward, it creates more space in the chest cavity, allowing the lungs to expand and draw in air.

When the diaphragm relaxes and moves upward, it reduces the space in the chest cavity, forcing air out of the lungs.

In summary, the lungs work by drawing air into the body, facilitating the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air and the blood, and expelling carbon dioxide-rich air from the body. This process is essential for maintaining proper oxygen levels in the body and removing waste products from cellular respiration.

Physiology of asphyxia

Asphyxia, also known as suffocation, happens when the respiratory system cannot function as it should to get enough oxygen into the body, which may be due to various conditions including but not limited to: airway obstruction, the constriction or obstruction of airways, such as from asthma, or simple blockage from the presence of foreign materials; from being in environments where oxygen is not readily accessible, such as underwater, in a low oxygen atmosphere, in high altitude, or in a vacuum; environments where sufficiently oxygenated air is present, but cannot be adequately breathed because of air contamination such as excessive smoke.

Asphyxia causes generalised hypoxia, which is a medical condition in which the tissues of the body are deprived of the necessary levels of oxygen, which may cause a lower than normal oxygen content in the blood, and consequently a reduced supply of oxygen to all tissues perfused by the blood.

Hypoxia by definition refers to a lower-than-normal level of oxygen, which is made up of hypo- (less) + oxygen + abstract noun ending -ia.

Actually, there are four different types of hypoxia: Hypoxic hypoxia which occurs at the lung level; hypemic hypoxia which refers to the reduced ability of the blood to carry oxygen; stagnant hypoxia which occurs at the circulatory level; and histoxic hypoxia which occurs at the cell level.

Oxygen is essential for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the primary source of energy for our cells. Hypoxia leads to a decline in ATP production, causing cells to function less efficiently.

In an attempt to compensate for the lack of oxygen, cells switch to anaerobic respiration, which is less efficient and produces less ATP. This process also generates lactic acid, which can lead to a decrease in blood pH (acidosis).

Prolonged oxygen deprivation can cause irreversible damage to cells, particularly in the brain and other vital organs. Neurons in the brain are particularly sensitive to hypoxia and can start to die within minutes.

When the brain doesn’t get enough oxygen, brain cells begin to die. Cell death happens within 5 minutes of low oxygen and brain death occurs after 10 minutes without oxygen.

As the body struggles to cope with the lack of oxygen, various physiological responses are triggered. These include an increase in heart rate and blood pressure, as well as the constriction of blood vessels in non-essential organs to divert blood flow to the brain and heart.

Hypoxia causes symptoms such as confusion, restlessness, difficulty breathing, rapid heart rate, headache, rapid breathing, anxiety, and in case of severe hypoxia, it causes slow heart rate, extreme restlessness, and bluish skin.

If oxygen deprivation continues, the individual may lose consciousness and eventually suffer brain damage or death.

What is positional (postural) asphyxia?

Positional asphyxia, also known as postural asphyxia, is a form of asphyxia that occurs due to body position, resulting in the restriction of respiration and consequently leading to oxygen deprivation (hypoxia) in the body.

It is a rare but potentially fatal condition that has been reported in various scenarios, including restraint-related deaths, drug overdoses, and even in seemingly innocuous situations like sleeping in an awkward position.

The term “positional asphyxia” was first used in 1992 by Bell et al. who examined 30 cases of asphyxia-related death in a nine-year period in Broward, Florida. Their study found that most often, the deceased individuals were found in positions that obstructed the upper airway. Four of the thirty cases were reportedly found in positions that restricted chest and diaphragm movement, suggesting perhaps the cause of death could have been from hypoventilatory respiratory failure. No other significant contributors to death were found in these subjects.

Positional asphyxia occurs when the body’s position compresses the chest or abdomen, limiting the movement of the diaphragm, thus restricting the ability to breathe as diaphragm has to contract and relax without limitation to allow the lungs to draw in air and letting air out.

Types of physical restraint which carry the risk of positional asphyxia

There are various physical restraint techniques used in different settings such as healthcare facilities, schools, prisons, etc. These techniques may be listed as restricted escort, standing restraint, seated restraint, supine restraint and prone restraint.

NHS’ Safe use of Physical Restraint Techniques document says that in situations where physical restraint is deemed necessary, staff should aim to utilise a seated approach: “Where possible, restraining patients in prone positions should be avoided.

“In exceptional situations where the restrained person needs to be held in prone position for the safety of themselves and/or others, this should be for the shortest time possible. “

Prone restraint refers to a physical restraint in a chest down position, regardless of whether the person’s face is down or to the side while supine restraint involves a physical restraint where the patient is held on their back.

Prone restraint is commonly used in healthcare and educational settings to manage aggressive or self-harming behaviour. However, it has also been employed by law enforcement during arrests to control resistant individuals.

Although NHS’s current guidance states that all restraint positions should be considered to present equal risk, research conducted on the subject says otherwise.

The highest risk of positional asphyxia is found in prone/face down restraint technique as research has shown that participants restrained face down with the body weight of the restraining persons pressed on their upper torso and/or in a flexed restraint position showed a significant reduction in lung function.

However, participants restrained flat on the floor, prone or supine, showed non-significant reductions in forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume compared with the standing control position.

So, applying body weight on the upper torso while restraining has been shown to create quite a difference in the lung function of the individual in face down position.

Therefore, proper training and adherence to guidelines are needed to ensure safe and appropriate use of these techniques as research has shown that some, but not all, prone restraint positions show significant restriction of lung function.

UK’s new guidelines on the use of restraint

In response to the concerns in regards of this subject, the UK’s College of Policing has issued new guidelines on the use of restraint, emphasizing the importance of monitoring detainees’ breathing and the dangers of positional asphyxia.

The guidelines also highlight the need for officers to be trained in recognizing the signs of positional asphyxia and how to respond appropriately.

College of Policing’s Authorised Professional Practice says: “All police officers and custody staff should be aware of the dangers of positional asphyxia and restraining people experiencing acute behavioural disturbance (ABD), which is a medical emergency.

“A custody office is a controlled environment and the overriding objectives should be to avoid using force in custody.”

Despite these new guidelines, concerns remain about the implementation and enforcement of these practices across the country.

In a 2020 report, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) found that only 34% of police forces in England and Wales had provided adequate training on positional asphyxia to their officers.

Efforts to reduce restrictive practices to prevent risks such as positional asphyxia necessarily led to efforts to provide more specific training on safer restraint since there are some specific circumstances to all restraints.

An example of a specific circumstance is drug use since an examination of deaths in or following police custody found that restraint is significantly more likely to be used in a drug-related arrest than during a non-drug-related case.

The examination found that “of the 56 drug-related cases of death in or following custody, 43% had involved restraint of the individual. Most commonly, the restraint technique involved officers holding down the individual.”

The Authorised Professional Practice also says that “individuals experiencing mental illness who are restrained, particularly due to violence, need to be considered as a medical emergency and taken to hospital as they are at increased risk of ABD.”

Using physical restraint in private security

There have been many concerns in regards of the use of physical restraint due to its, sometimes fatal, consequences. And these concerns have been voiced not only for police officers, but also for private security professionals such as custody officers, security officers, and door supervisors as there have been controversial cases where private security professionals’ interventions contributed to death of individuals.

Such is Jason Lennon’s case, during the proceedings of which the jury found that “Jason Lennon died of a cardio respiratory arrest which he suffered at the Excel Centre in London on 31 July 2019 due to restraint in the prone position following an acute psychotic episode.”

During the proceedings, the jury heard that on the morning of 31 July 2019, Jason Lennon was seen behaving strangely and recklessly in and around London’s ExCeL centre, potentially putting himself and others at risk. He was in fact experiencing an acute psychotic episode which is a mental health concern.

Just after 7.30am, Secure-Ops Security guards inside the venue brought Jason to the ground and restrained him with considerable force and in the prone position for about 5 minutes.

The Metropolitan police arrived on the scene at around 7.35am and found Jason unresponsive. They commenced CPR at around 7.39am. An ambulance arrived on the scene and Jason was taken to Newham General Hospital where he was pronounced dead at 9.31am.

The jury ultimately concluded that the security guards had used excessive force in effecting the restraint and had failed to respond to the fact that Jason was becoming unresponsive.

And these were Security Industry Authority (SIA) licensed security staff who were trained that ground restraint, particularly in the face down position, is dangerous and should be avoided.

The proceedings took place at the beginning of 2022 and this was the fourth inquest in the previous year in which restraint by security staff has been criticised and found to contribute to a death.

Private security professionals’ use of physical restraint

Although lawful in certain circumstances, such interventions of private security professionals will require high levels of justification and training.

The training always starts with emphasising the importance of only using physical restraint techniques as a last resort, in other words when other options have failed or likely to fail and when it is not possible or appropriate to withdraw, because the use of physical restraint can:

Increase risks of harm to staff and customers,

Result in prosecution of staff if use of force was unnecessary, excessive, or in any other way unlawful,

Lead to allegations against staff and potentially loss of licence and/or employment.

Any forceful restraint can lead to medical complications, positional asphyxia leading to sudden death or permanent disability especially where situational and individual risk factors are present.

It is also important to recognise the potential stress and emotional trauma individuals can suffer in situations where physical restraints are used.

This can be particularly difficult for individuals who have prior experience of abuse and trauma. Staff must respect the dignity of individuals they are managing, however challenging they may find them.

Reducing restrictive practices through training and risk assessment

It is highly important to familiarise oneself with legislation and professional guidance and standards relevant to the area of employment.

Training will enable security professionals: to make dynamic risk assessments to assess threat and risks of assault to staff and harm to others through a decision to use physical restraint or not; to evaluate options available and inform decisions whether to intervene, when and how; to identify when assistance is needed; and to continuously monitor for changes in risks to all parties during and following an intervention.

Assessment of risk factors, situational and individual factors that increase the risk is of crucial importance.

Risk factors include nature of the restraint that can increase risk, restraint technique, position held and duration of restraint.

Assessing situational and individual factors that increase the risk are even more important in making dynamic risk assessments in various settings.

For example, using physical restraint techniques on a child in a custodial setting would differ from using physical intervention methods on an adult in a criminal setting where the individual may pose an immediate danger to themselves and others.

Some groups are especially vulnerable to harm when subjected to physical contact and restraint including children and young people, older adults and individuals with mental health difficulties. Staff likely to physically intervene with people from vulnerable groups should receive additional training.

SIA guide to safer restraint

Therefore, learning about safe restraint is crucial to reduce the risk of positional asphyxia when restraint is unavoidable to prevent people harming themselves or others.

The Authorise Professional Practice document issued by the College of Policing says: “There is an increased risk of causing positional asphyxia when restraining those of particularly small or large build or those who have taken drugs, medications (anti-psychotics) or alcohol.

“People restrained in the prone position should be placed on their side or in a sitting, kneeling or standing position as soon as practicable. “

Security Industry Authority (SIA) issued a guide to safer restraint to train private security operatives on the risk of positional asphyxia.

According to the SIA guide, warning signs that should be closely monitored during restraint include: Inability or difficulty in breathing; a sudden increase, or decrease, in resistance; complaining of difficulty breathing; feeling sick or being sick; becoming limp, unresponsive, or apparently unconscious; respiratory or cardiac arrest; swelling around the face and neck and a blue colour especially around lips; small blood spots appearing on the head, neck and chest areas; noticeable expansion of the veins in the neck.

Security operatives should check vital signs using ABC method when they have someone under restraint:

Airway – make sure their airway is not obstructed

Breathing – check that the person is breathing normally

Circulation – check that you can detect heartbeat and pulse.

SIA guide says: “Continuously communicate with the person restrained to help calm and reassure them, and ensure they can talk easily and are OK. De-escalate the restraint and use of force at the earliest opportunity.”

The guide also warns about things to avoid:

“Don’t restrain a person on the ground in a way that might affect their ability to breath. In particular, don’t apply weight or pressure to a person’s back while they are lying on the ground.

“Don’t restrain a person leaning forward in a sitting position, as this can obstruct their airway.

“Don’t restrain a person by bending them forward from the waist and keeping them in that position, as this restricts the diaphragm and ability to breath.

“Don’t put weight on a person’s chest, back or stomach, as this causes stress to the muscles used in breathing, and prevents the normal movement of the diaphragm and ribcage.”

Security operatives should immediately release restraint when they suspect asphyxiation and treat it as a medical emergency.

They should call for urgent medical assistance and provide appropriate first aid/CPR.

(Diagram 1: How lungs work)

(Diagram 2: How we breath)

(Diagram 3: Effects of hypoxia, by Mayo Clinic via Flickr)